by Rev. Anthony Dodgers

July 30 is the commemoration of Robert Barnes, Confessor and Martyr. But his name might not be well known, even among those who study the Lutheran Reformation in Germany. This is probably because, unlike most Lutherans of the 16th century, Barnes was not German. He was an Englishman, who served his king, preached the pure Gospel to his countrymen, and ultimately, laid down his life as a witness to Jesus Christ.

Robert Barnes was born in 1495 in Norfolk, England. In 1514, he began studying at Cambridge University and also became an Augustinian friar (the same order that Martin Luther joined in Erfurt, Germany). Barnes was a bright student and a dedicated friar. He eventually earned his doctorate in divinity and was made prior of the Augustinian House in Cambridge. He was also a member of a scholarly group that regularly met at a local pub called The White Horse Inn. These men followed humanist scholars like Erasmus. They were no longer satisfied by the medieval scholasticism, they were disgusted by the corruption of bishops, and they were suspicious of church teachings that seemed to contradict the New Testament. They wanted reform. Within this circle, Barnes was introduced to the writings of Luther.

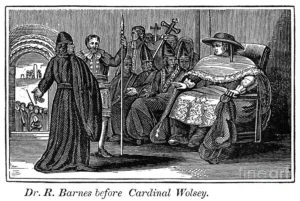

Barnes began urging reform in his sermons, and consequently, he was tried for heresy and put under house arrest in London for almost two years. Still, he took advantage of his new location by helping in the clandestine distribution of Lutheran books and Tyndale’s English Translation of the New Testament. In November 1528, he was warned that the authorities were planning his execution, so he fled to the continent and finally reached Wittenberg in 1530.

Now Robert Barnes truly became a Lutheran. He stayed in Wittenberg for over a year, living in the home of Johannes Bugenhagen and studying under Martin Luther himself. Around the time of his arrival, the Lutherans were returning from the Diet of Augsburg, so Barnes would have been able to read and discuss the Augsburg Confession and its Apology with their author, Philip Melanchthon. In 1531, Barnes published his most important work: A Supplication to King Henry VIII. This was an attempt to defend himself against the English bishops and to convince King Henry of Lutheranism. The pure Gospel shines through Barnes’s pen: “Scripture says that faith alone justifies because it is that through which alone I cling to Christ. By faith alone I am partaker of the merits and mercy purchased by Christ’s blood. It is faith alone that receives the promises made in Christ. Through our faith the merits, goodness, grace, and favour of Christ are imputed and reckoned to us.”[1]

Through his writing, Barnes came to the notice of Thomas Cromwell (the new and Protestant English Chancellor). By this time, Henry VIII wanted a divorce from his first wife, and when the pope denied him, he turned to the Protestants. Barnes was appointed to carry Luther’s reply to Henry VIII on the divorce issue and so returned to England under safe conduct from the king. The news was not good, however, as Luther rejected Henry’s case for divorce, and the political climate was unsafe, so, Barnes returned again to Germany the following year. This was the beginning of a precarious relationship between Robert Barnes and King Henry. Barnes needed protection and acceptance in England in order to teach and preach. Henry needed a willing and loyal subject who had strong ties to the Lutheran princes of Germany. Cromwell was promoting an alliance between England and the Lutheran Smalcald League, and this meant that Henry had to accept the Augsburg Confession. Theologians from both sides met for discussion, including Robert Barnes and Philip Melanchthon.

However, the official doctrine in England remained primarily Roman Catholic. In Lent 1540, Robert Barnes preached a reformation sermon in London and was imprisoned in the Tower. When Cromwell himself fell out of favor with the King and was arrested in June, Barnes lost his protector. On July 30, Barnes and two other Protestant preachers were burned to death. To the very end, Barnes remained steadfast in his faith and was able to give a thoroughly Lutheran final confession: “There is none other satisfaction unto the Father, but this [Christ’s] death and passion only… That no work of man did deserve anything of God, but only [Christ’s] passion, as touching our justification… For I knowledge the best work that ever I did is unpure and unperfect… Wherefore I trust in no good work that ever I did, but only in the death of Jesus Christ.” [2]

When the news of Robert Barnes’s martyrdom reached the continent, Melanchthon was horrified and Luther criticized Henry. Barnes had confessed the doctrine of justification by faith alone and so was martyred by a king who was an enemy to that most precious doctrine of the Gospel. Here is what Luther wrote concerning the Lutheran martyr of England:

“This Dr. Robert Barnes we certainly knew, and it is a particular joy for me to hear that our good, pious dinner guest and houseguest has been so graciously called by God to pour out his blood and to become a holy martyr for the sake of His dear Son… He always had these words in his mouth: Rex meus, regem meum [“my king, my king”], as his confession indeed indicates that even until his death he was loyal toward his king with all love and faithfulness, which was repaid by Henry with evil. Hope betrayed him. For he always hoped his king would become good in the end. Let us praise and thank God! This is a blessed time for the elect saints of Christ and an unfortunate, grievous time for the devil, for blasphemers, and enemies, and it is going to get even worse. Amen.”[3]

The Rev. Anthony Dodgers is pastor of Immanuel Lutheran Church, Charlotte, Iowa.

Other Sources

Schofield, John. Philip Melanchthon and the English Reformation. (Burlington: Ashgate, 2006).

Tjernagel, Neelak S. Henry VIII and the Lutherans. (St. Louis: Concordia, 1965).

[1] Neelak S. Tjernagel, ed., The Reformation Essays of Dr. Robert Barnes (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 1963), 36.

[2] George Pearson, ed., The Remains of Myles Coverdale, Bishop of Exeter (Cambridge: University Press, 1846), 355, 379, 383, 397.

[3] “Preface to Robert Barnes Confessio Fidei (1540).” Translated by Mark DeGarmeaux from pp.449-51 of vol. 51 of D. Martin Luthers Werke: Kritische Gesamtausgabe (Weimar: Hermann Bohlau, 1883-). Found in Treasury of Daily Prayer, Scot Kinnaman, ed. (St. Louis: Concordia, 2008), 574-5.