by Rev. Anthony Dodgers

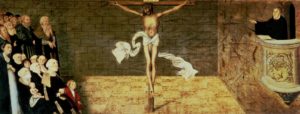

On Invocavit Sunday (the First Sunday in Lent), March 9, 1522, Martin Luther stepped into his pulpit in the City Church. His hair was no longer tonsured but he still wore the black cowl of the Augustinian friar. Over the course of that first week in Lent he preached a sermon every day. The focus of these sermons was to correct the radical reforms that had been advanced by Carlstadt and Zwilling, which had troubled the consciences of people who did not yet know the Gospel. Luther was confident that if the Word was preached, it would do the necessary work in creating faith and reforming the Church.

The Gospel reading for Invocavit is Satan’s temptation of Jesus in the wilderness. While Luther never explicitly refers to the text, he warns his hearers of succumbing to the devil’s temptations when they neglect the Word of God. It is not enough to listen to your human teachers, whether it be the pope or Carlstadt or Luther. “Everyone must stand on his own feet and be prepared to give battle to the devil. You must rest upon a strong and clear text of Scripture if you would stand the test” (AE 51, 80). How will you answer the devil when he accuses you of sin and you face death? Will your words and actions in this life cause you or others uncertainty? Here we see the ultimate concern Luther had for the state of a Christian conscience. His overall evaluation of the Wittenberg reforms was that they had done the right things but in the wrong ways (AE 51, 73). It is not enough to do the right things, but consciences must be instructed to know why they right and so have confidence and peace based on God’s Word.

As the preacher called by God to this congregation, Luther is not merciless, but he also pulls no punches. He says, “Here one can see that you do not have the Spirit, even though you do have a deep knowledge of the Scriptures” (AE 51, 74). He sees that their deep knowledge has not actually benefited their neighbor. Knowledge of the Scriptures must be used to instruct consciences. It is in this teaching of the Gospel that the Spirit is at work to create certainty of faith. Luther concluded his first sermon with a call to action and a warning:

Let us, therefore, feed others also with the milk which we received, until they too, become strong in faith. For there are many who are otherwise in accord with us and who would also gladly accept this thing [the reformation], but they do not yet fully understand it – these we drive away. Therefore, let us show love to our neighbors; if we do not do this, our work will not endure (AE 51:74).

Throughout the week, Luther emphasized the powerful working of God’s Word. He constantly directs his hearers to listen to the sure commands and promises of God. The Word alone should be the source of their confidence in faith and life. In fact, Luther is surprised that they would suppose one could create true Christians by force and mere outward regulation. It was obvious to Luther, and should be to all Christians, that it is not in the power of man to create faith. Here Luther explains the preacher’s relationship to his hearers:

I can get no farther than their ears; their hearts I cannot reach. And since I cannot pour faith into their hearts, I cannot, nor should I, force any one to have faith. That is God’s work alone, who causes faith to live in the heart. Therefore we should give free course to the Word and not add our works to it. We have the [right to speak] but not the [power to accomplish]. We should preach the Word, but the results must be left solely to God’s good pleasure (AE 51, 76).

Luther recognized rightly that far from creating faithful Christians, coercion created hypocrites. If the heart is not truly converted, it does not matter what the lips say or what the hands do. In the end, an unbelieving person saying or doing the right thing does far more evil than a trusting soul who still struggles to bring his practice in line with his faith.

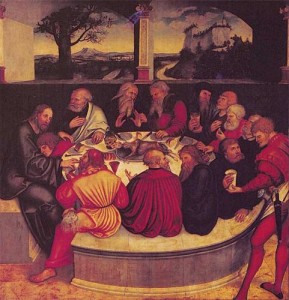

The example of Communion in both kinds is instructive. Luther would not have the blood of Christ forced upon the laity, but it should be offered and extolled as it is included in Christ’s institution. He desired to let the Word convert and move the people toward a godly desire for the blood of Christ, so that they would not fear this precious gift. But, Luther argues, when the results are not left to the Word, then the sacrament becomes for me an outward work and a hypocrisy, which is just what the devil wants. But when the Word is given free course and is not bound to any external observance, it takes hold of one today and sinks into his heart, tomorrow it touches another, and so on. Thus quietly and soberly it does its work, and no one will know how it all came about (AE 51, 90).

Luther’s faith in the power of God’s Word was neither naïve nor an excuse for inaction. He saw the efficacy of the Word proven in his own life and ministry, and he counseled his followers to recognize what had already been achieved by preaching. For Luther, the true reformation was already underway and owed everything to God’s Word:

Take myself as an example. I opposed indulgences and all the papists, but never with force. I simply taught, preached, and wrote God’s Word; otherwise I did nothing. And while I slept, or drank Wittenberg beer with my friends Philip and Amsdorf, the Word so greatly weakened the papacy that no prince or emperor ever inflicted such losses upon it. I did nothing; the Word did everything (AE 51, 77).

Luther’s example shows what comfort a firm confidence in the Word can give. With true faith in God’s trustworthy promises and activity, the Christian can freely enjoy God’s work and gifts, including the gift of a pint of good beer with good friends. “Quietly and soberly [the Word] does its work,” says Luther. “I did nothing; the Word did everything.” This is how a reformation should begin. Far from a radical revolution, Luther’s reformation was a patient reliance on the activity of God’s Word and the Gospel’s ability to give growth and bear fruit.

The Rev. Anthony Dodgers is pastor of Immanuel Lutheran Church in Charlotte, Iowa.