by Mr. Jonathan Swett

Ambrose of Milan (c. 340-397) is known as the father of Latin hymnody and standardized the form known in modern English hymnody as “Long Meter”—four lines of iambic tetrameter. Ambrose was a staunch opponent of Arianism and crafted hymns during this struggle that were meant for congregational participation and are characterized by their simplicity, austerity, and objectivity. Though many other hymns have been attributed to Ambrose, it is likely that several of these “Ambrosian hymns” were written by anonymous imitators and disciples. Veni, Redemptor genitum (“Savior of the Nations, Come”) is one of a few hymns that is evidentially attributed to Ambrose. Martin Luther, also writing during a period of great adversity, provided a literal translation of this text into German from which many English translations have since been produced. Fred Precht rightly says of the hymn: “In the history of hymnody this hymn is the Advent hymn par excellence.” [1]

The basic thought and theological implications of “Savior of the Nations, Come” include longing or expectation for a Savior; the work of Jesus and His triumph over death; and life in the light of Christ. It is the appointed Hymn of the Day for the first Sunday in Advent in both the one and three-year lectionary.

The poetic meter is trochaic because it follows the alternating pattern of a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable. The syllabic meter is 77 77 (each phrase has seven syllables) and the rhyme scheme is AABB (the last syllable of each ‘A’ phrase rhymes, as do the ‘B’ phrases).

Hymn analysis becomes more complex when searching for poetic devices. In The Anatomy of Hymnody Austin Lovelace describes: “There is more subtlety and craftsmanship in great hymns than meets the eye (or the ear). Poetic devices are sinew and muscle which surround the skeletal meter, but if the rippling muscles and effects are obvious and distracting, the cleverness of the poet kills the spiritual intent of the hymn. To say this is not to disparage or discourage the use of poetic devices, for great hymnody could not exist without them. There are countless types of metaphors, rhetorical devices, figures of speech, and forms of repetition which are to be found in abundance in the hymnal.”

Lovelace provides twenty-eight examples of different poetic devices in his book and admits his list is by no means exhaustive. Here are some that I observed in “Savior of the Nations, Come” (LSB 332):

Anaphora—Repetition of a word at the start of successive lines.

“Glory to the Father sing,

Glory to the Son, our king,

Glory to the Spirit be

Now and through eternity.” (Stanza 8)

Hypotyposis— A vivid description designed to bring a scene clearly before the eyes.

“From the manger newborn light

Shines in glory through the night.

Darkness there no more resides;

In this light faith now abides.” (Stanza 7)

Oxymoron—Combining for special purposes words which seem to be contradictory.

“God of God, yet fully man” (Stanza 4, 3rd phrase)

-Paradox—A statement containing two opposite ideas.

“Here a maid was found with child,

Yet remained a virgin mild.” (Stanza 3, 1st and 2nd phrase)

Simile—Unlike objects are compared in one aspect.

“From the manger newborn light

Shines in glory through the night.” (Stanza 7, 1st and 2nd phrase)

Other examples of poetic devices that you may be more familiar with are alliteration, metaphor, personification, rhetorical question, etc.

A helpful tool in Lutheran Service Book is the Scripture reference provided for each hymn. The references provided for LSB 332 are John 1:1, 14 and Luke 2:30-32.

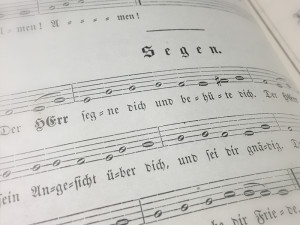

The tune which accompanies “Savior of the Nations, Come” is Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland (also known as Veni, Redemptor genitum) which is based on a plainsong melody first found in the 12th or 13th century. Luther’s translation and simplified melody first appeared together in Eyn Enchiridion (Erfurt, 1524) and Walter’s Geystliche Gesangk Büchleyn (Wittenberg, 1524).

Analysis of the tune is more technical in nature and likely not as easily understood by the musically untrained. The form of the melody is ABCA and it is presented in a minor tonality utilizing diatonic (contained in the scale of the home key) notes. The melodic intervals are primarily steps and the tessitura (range) is only a fifth. Rhythmically, each phrase consists of quarter, eighth, and half notes, with one dotted-quarter note making an appearance in the second phrase. The tune is easily notated in common meter (or 4/4 time) in which there are four beats in each measure and the quarter note receives one count. The decisive character of the hymn’s trochaic text relates comfortably to the approachable yet strong minor tonality tune.

Provided below is a format I learned at Concordia University-Chicago and used to prepare this article—perhaps you may also find it useful for exploring other great hymns in the treasury of Lutheran hymnody!

Mr. Jonathan A. Swett is Kantor of Our Savior Evangelical Lutheran Church and School, Hartland, Mich.

HYMN ANALYSIS FORM

Hymn #:

TEXT

Name of hymn:

Author:

Dates:

Background information:

Basic thought of hymn:

Syllabic and poetic meter:

Rhyme scheme:

Poetic devices and their location:

Scripture references:

Theological implications:

TUNE

Tune name:

Composer/arranger:

Dates:

Background information:

Basic type of tune:

Form:

Melody:

Rhythm:

Text/tune relationship:

PERSONAL THOUGHTS/REFLECTION:

Bibliography:

Eskew, Harry, and Hugh McElrath. Sing with Understanding: An Introduction to Christian Hymnody. Nashville: Church Street Press, 1995.

Lovelace, Austin. The Anatomy of Hymnody. Chicago: G.I.A. Publications, Inc., 1965.

Precht, Fred. Lutheran Worship: Hymnal Companion. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1992.

[1] Stulken, Marilyn Kay. Hymnal Companion to the Lutheran Book of Worship. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981.