by Rev. Dr. Mark Birkholz

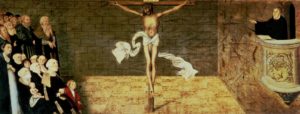

The Reformation was not just a movement among the cultural and religious elite. Ordinary people of Germany and beyond were captivated by the gospel, newly presented to them by Luther and the Reformers. The laity were engaged by the gospel in many different ways, through newly composed German hymns, the German translation of the Bible, and the woodcuts and illustrations of artists involved in the Reformation. One of the primary means for the spread of the gospel in the Lutheran Church has been through preaching.

Martin Luther was a preacher, and delivered thousands of sermons throughout the course of his life. Many of these sermons were published and circulated in his day.[1] In fact, the Small Catechism began as series of sermons given by Martin Luther.[2] Luther’s preaching, however, was different from the preaching of his day. Lutheran preaching would eventually be characterized by the proclamation of the gospel by those called by God as His representatives.

In most churches today, the titles “pastor” and “preacher” are synonymous. You expect your pastor to be the one preaching to you from the pulpit on a regular basis. But this was not always the case in the late Middle Ages. Most parish pastors were poorly educated and unable to deliver a sermon. It was not unusual for a parish to pay a traveling monk or scholar to preach for them.[3] These sermons were typically about an hour in length, and focused on ethical duties and issues of morality rather than on grace of God.

The Lutherans were quick to recognize that preaching is an inseparable component of the pastoral office, so that the German term for the office of the holy ministry is Predigtamt or “Preaching Office.” (AC V; Tr 10; cf. AC XVIII:5-8) The pastor is the man God sends to proclaim His Word, and the Holy Spirit then works through this preached Word to create faith. As St. Paul writes:

How then will they call on him in whom they have not believed? And how are they to believe in him of whom they have never heard? And how are they to hear without someone preaching? And how are they to preach unless they are sent? . . . So faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ. (Romans 10:14-15a, 17; cf. AP XXIV:31-33)

Preaching is done by one called by God through the church to speak on His behalf. (Luke 10:16; AP VII & VIII:28, 47) As you hear the preacher you are hearing Jesus speak to you, and the Holy Spirit is working in you to create and strengthen faith. Luther said, “Yes, I hear the sermon; but who is speaking? The minister? No indeed! You do not hear the minister. True, the voice is his; but my God is speaking the Word which he preaches or speaks.”[4]

Preaching, therefore, is not just instruction or entertainment. Preaching is a means of grace. It is sacramental. A good sermon is not just a message that you find interesting and educational, but one in which God’s word of Law convicts you of your sin and His word of Gospel comforts you and strengthens your faith, delivered by the man God has sent to you as His spokesman.

It is the responsibility of the church to pray to the Lord that He would send faithful preachers to proclaim His life-giving Word. In the inside cover of the Lutheran Service Book you will find this prayer “For blessing on the Word”:

Lord God, bless Your Word wherever it is proclaimed. Make it a word of power and peace to convert those not yet Your own and to confirm those who have come to saving faith. May Your Word pass from the ear to the heart, from the heart to the lip, and from the lip to the life that, as You have promised, Your Word may achieve the purpose for which You send it; through Jesus Christ, my Lord. Amen.

The Rev. Dr. Mark Birkholz is pastor of Faith Evangelical Lutheran Church, Oak Lawn, Ill.

[1] See Timothy J. Wengert, Introduction to The 1529 Holy Week and Easter Sermons of Dr. Martin Luther (St. Louis: CPH, 1999), 11-13.

[2] See Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions, Paul T. McCain, et al, eds. (St. Louis: CPH, 2005), 335-36.

[3] For more background on the state of preaching in the late Middle Ages, see Richard J. Serina, Jr., “Nicholas of Cusa and the Reformation of Preaching,” in Feasting in a Famine of the Word, Mark W. Birkholz, et. al, eds. (Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2016), 63-77.

[4] WA 47, 229 as found in What Luther Says: A Practical In-Home Anthology for the Active Christian, Ewald W. Plass, ed. (St. Louis: CPH, 1959), 1125.