by Rev. Christopher Maronde

“Distrusting completely our own wisdom…we humbly present to judgment of all those who wish to be here these theological paradoxes.” (AE 31:39)

It never happened. Many events were set in motion by Luther’s posting of the 95 Theses on October 31st, 1517, but ironically, not the very thing he intended. The 95 Theses were meant for theological debate, a debate that never occurred. Any expectation of a lively academic disputation was consumed by a firestorm that reached far beyond Wittenberg and Germany to the pope himself.

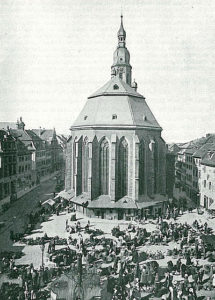

The debate that Luther called for was replaced by another debate; Luther’s father confessor and superior in the Augustinian order, Johann Staupitz, provided Luther the opportunity to defend and discuss his views at the April 1518 meeting of the general chapter of the Augustinians of Germany in Heidelberg. Staupitz wanted Luther to stay away from the more controversial topics of the 95 Theses, and instead asked him to simply talk about sin, free will, and grace. Luther obliged, preparing and presenting twenty-eight theological and twelve philosophical theses, with brief explanations.

Luther followed the instructions of Staupitz, never mentioning indulgences, purgatory, or the pope, but the theology of the 95 Theses, a theology that would be more and more developed as the Reformation proceeded, was front and center. In masterful fashion, Luther explored the assigned topics of free will, grace, and works, with one conclusion: we must trust in Christ, not ourselves. Despair of yourself!

“18. It is certain that man must utterly despair of his own ability before he is prepared to receive the grace of Christ.” (AE 31:40)

This thesis is the key to the entire disputation, and is what Luther is driving toward with the previous seventeen theses. There is nothing good in us because of sin, and any trust in our own abilities or our own works, is damning. We must be brought low before we can be exalted, we must be put to death before God makes us alive.

“Thus an action which is alien to God’s nature results in a deed belonging to His very nature: He makes a person a sinner so that He may make Him righteous.” (AE 31:51)

“To be born anew, one must consequently first die and then be raised up by the Son of Man.” (AE 31:55)

In his introduction to the theses, Luther sets the tone by despairing of his own wisdom, then he describes what he has to offer as ‘paradoxes,’ that is, truths set in tension that seem to our human reason to be contradictory.

“3. Although the works of man always seem attractive and good, they are nevertheless likely to be mortal sins.” (AE 31:39)

“12. In the sight of God sins are then truly venial when they are feared by men to be mortal.” (AE 31:40)

“14. Free will, after the fall, has power to do good only in a passive capacity, but it can always do evil in an active capacity.” (AE 31:40)

The paradoxes come down to one point: despair of yourself! One who puts their trust in their works, however good they are, will find that they are simply committing sins, while the one who in repentance and a consciousness of their own sin fears their works and clings to Christ, will find their sins not mortal at all, but venial. Here Luther is still working with the medieval distinction between mortal sins (sins that condemn to death and hell) and venial sins (minor sins that don’t condemn to hell). While he will drop that distinction as the years go on, the point is still clear: good works that are trusted in are actually sins, while good works done in repentant fear actually please God. It is only the one who has been humbled by his sins, who realizes the unworthiness of any of his acts, that can be used by God.

“If someone cuts with a rusty and rough hatchet, even though the worker is a good craftsman, the hatchet leaves bad, jagged, and ugly gashes. So it is when God works through us.” (AE 31:45)

Any who trust in their works should be driven to despair by these words: Even my best isn’t good enough? Indeed, my best good works are actually mortal sins? Yes, but Luther’s intent isn’t to leave us in despair. Instead, he seeks to honor Christ and preach the Gospel.

“To say that we are nothing and constantly sin when we do the best we can does not mean that we cause people to despair (unless they are fools); rather, we make them concerned about the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ.” (AE 31:51)

The Heidelberg Disputation is perhaps best known for the distinction that Luther draws between a ‘theologian of glory’ and a ‘theologian of the cross.’ But this distinction, as important as it is, cannot be divorced from the entire disputation. The theologian of the cross sees his works in the proper context, that is, he despairs of them and learns of God’s grace from the paradoxical work of the cross.

“Therefore the friends of the cross say that the cross is good and works are evil, for through the cross works are destroyed and the old Adam, who is especially edified by works, is crucified. It is impossible for a person not to be puffed up by his good works unless he has first been deflated and destroyed by suffering and evil until he knows that he is worthless and that his works are not his but God’s.” (AE 31:53)

“He who does not know Christ does not know God hidden in suffering. Therefore he prefers works to suffering, glory to the cross, strength to weakness, wisdom to folly, and, in general, good to evil.” (AE 31:53)

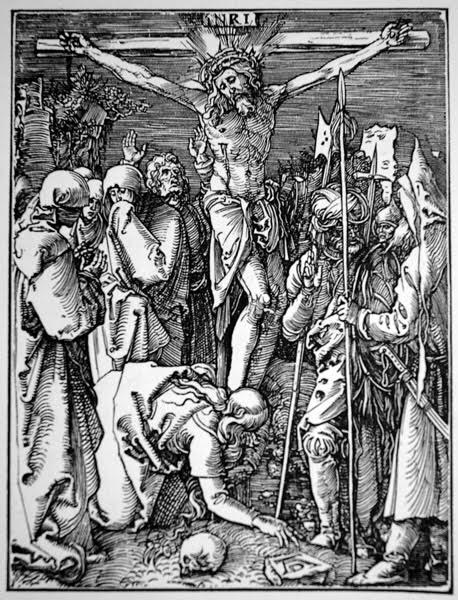

This distinction between the theologian of the cross and the theologian of glory is the crowning paradox, and a natural conclusion to be drawn from the eighteenth thesis. God Himself did the most paradoxical act in history, bringing life and salvation through the bloody, humiliating death of His Son upon the cross. Every other paradox flows out of the paradox of the cross: we apprehend the things of God not in glory, but in the suffering and death of Jesus.

“25. He is not righteous who does much, but he who, without work, believes much in Christ.” (AE 31:41)

“26. The law says, ‘do this,’ and it is never done. Grace says, ‘believe in this,’ and everything is already done.” (AE 31:41)

The Rev. Christopher Maronde is associate pastor of Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Lincoln, Neb.