by Rev. Matthew Zickler

“Exsurge Domine!” “Arise, O God!” With that Latin phrase the Roman commission commenced the papal bull drafted to excommunicate the “heretic,” Martin Luther. The draft was delivered to Leo X on May 2, 1520 as he was at a hunting lodge retreating in pursuit of wild boars. The context was fitting, as the bull continued by pleading for God to arise and act “against the foxes and wild boar who are destroying the vineyard of the Lord, who had bestowed jurisdiction over it to Peter and his successors.”[1] For the Roman Curia, Luther and his writings had gone too far. They had pushed the limits of what was acceptable for teaching in the church and now must be understood as heresy.

The bull was dated June 15th of 1520, and listed forty-one statements from Luther which it considered deviations from church doctrine. These dealt with such sundry topics as penance, indulgences, sin remaining after baptism, confession, faith, the demand for both kinds in the sacrament, etc.[2] Likewise it also called for all of Luther’s books to be burned so as to prevent others from reading them and being infected by them. It also gave Luther sixty days to recant everything.

The bull made life harder not just for Luther, but anyone showing any sympathy and protection for his well-being, as they were listed under its auspices too. This put such figures as Luther’s Elector, Frederick the Wise, in a most precarious position since Luther’s protection came first and foremost from him.

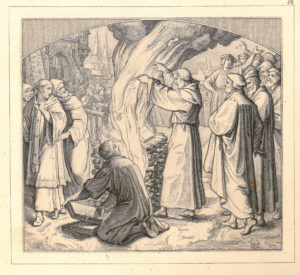

So, what did Luther do when the bull arrived in Wittenberg in October of that same year? Immediately he did nothing, at least not necessarily anything with the bull per se. He continued to write and in his writings he persisted in professing the assumption that this bull was the work of his nemesis, John Eck. He wrote as though the pope were innocent in this, and did so in a fashion which conveyed his intention and desire to remain a part of the church rather than to create division. However, when the sixty days came to an end, Luther did not stand idly by. Making a great statement, one in direct reciprocation to the burning of his works, he gathered a crowd in Wittenberg and burned the canon law of the church. This statement made the point that these teachings were the heretical ones. These teachings, not Luther’s writings, were in direct opposition to Scripture. In his great act of defiance, he then also set ablaze the bull, Exsurge Domine.

When this act of defiance is discussed, often it is associated with Luther’s most historic moment of boldness: the Diet of Worms where he made the confession, “Here I stand!” However, something should be clarified. The burning of the bull was not something Luther did lightly, or with great pomp necessarily. He later told his friend and superior Johann von Staupitz that he did this while “trembling and praying.”[3]

Such an attitude should give us insight into Luther’s motivation. How so? Often Luther is considered a sort of loudmouthed insolent; the first punk rocker fighting against the establishment keeping him down; the first rebellious advocate for the individual over and against the institution. But even in such an insubordinate act, Luther did not act for his own interest. Luther did not act to rebel for the sake of rebellion. He did not operate with the concern for the individual above all. Nor did he split from the church of his own accord to start something better.

Rather, he saw these things as necessary consequences of his duty as a doctor of the church: to preach and teach the Scriptures and rebuke any who taught otherwise. When Luther burned the bull Exsurge Domine he was not doing so as an impudent demonstration of the power of one, he was doing so as a Christian bound by God’s Word, as a professor confessing that Word publicly, just as he had vowed to do. In fact, if one would like true insight into what was happening he should look no further than what Luther later said in describing the Fourth Commandment: “We should fear and love God so that we do not despise or anger our parents and other authorities, but honor them, serve and obey them, love and cherish them.” Luther saw his duty under the authority of the Word as to “hold firm to the trustworthy word as taught, so that he may be able to give instruction in sound doctrine and also to rebuke those who contradict it” (Titus 1:9).

In our day, we should take a lesson from this. While the individual is rightly granted amazing care under the watchful and loving eye of our gracious Lord Jesus, His concern for us isn’t that we be able to express ourselves at any cost. His concern, likewise, is not that we demand whatever our sinful flesh might crave. His concern is not that we make sure the oppressive “man” knows that he cannot hold us down. Rather our Lord’s concern would be that our sinful selves be drowned and die that a new man would arise by the grace won for us on the cross, that we cling to the promise that, by faith alone, He has fulfilled the entire law for us, being crucified for our transgression and raised for our justification. This is the very Gospel that Luther sought to defend and confess in the burning of Exsurge Domine. May our Lord grant us such faith and norm our actions and our confession by the same rule: sola fide, sola gratia, sola scriptura, solus Christus, soli Deo Gloria!

The Rev. Matthew Zickler is pastor of Grace Lutheran Church, Western Springs, Ill.

[1] Martin Brecht, Martin Luther: His Road to Reformation, 1483-1521 (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1993), 391.

[2] Ibid

[3] Ibid., 424. Cf also LW 48:192.