by Deac. Carolyn Brinkley

It’s Jesus! Nearly everyone who sees the magnificent self-portrait of Dürer has the same reaction viewing it as an icon of Christ Himself. Why is this? What was Dürer trying to achieve? He obviously put a great deal of time, thought, and skill into the painting, but what was his purpose?

It would appear that he intended to leave the painting to posterity as it is dated 1500, with his famous AD monogram underneath, a play on his own initials and Anno Domini, the year of our Lord. On the right, his Latin inscription translates, “Thus I, Albrecht Dürer from Nürnberg, painted myself with indelible colors at the age of 28 years.” But is there something more? Dürer was the one of the first artists to paint self-portraits. But why would he paint in the typical medieval tradition of picturing Jesus in full frontal view and use himself as the visage of Christ? The answer is: we don’t know!

Interestingly, during the century following the creation of the self-portrait, there is no mention of anyone viewing it with religious connotations. Rather, acclaim was given to the exquisite technique seen in the textures of the fur, hair, and eyes. However, since then, art critics of later times have looked backwards speculating on Dürer’s motives. The harshest theory pronounces Dürer as arrogant, egotistical, and blasphemous for representing himself as the Savior. This view is highly unlikely as his writings and life show Dürer as a devout Christian coming from a highly pious family.

Another explanation is Dürer’s desire to elevate the status of the German artist from simply a craftsman to the level of genius as he had witnessed in his travels to Italy. After his journeys south, he sought to improve the artists’ level in German society. Thus, Dürer dresses himself in the elegant fur robe of a nobleman while suggesting the important and necessary tools of the artist in his clear, direct, discerning eyes and his well-formed fingers holding the fur for the paintbrush.

Some see the masterpiece as the artist’s way to imitate Christ in his life and work as set out in Thomas a Kempis’s De Imatatione Christi.[i] This would hold true to Dürer’s belief that his creative powers were an expression of God, as expressed in his own words, “…We shall all gladly learn, for the more we know so much more do we resemble the likeness of God who verily knoweth all things.”[ii].

It was not until after the artist’s death that the self-portrait was hung in the town hall of Nürnberg for public display. Up until that time it was kept privately in the Dürers’ home. Some think it was used to teach students and to demonstrate his skill to clients. However, this interpretation falls short, as Dürer’s interest did not lie in commissioned oil paintings. He disliked having patrons and preferred to busy his workshop with woodcuts and engravings because they were not only more profitable, but he was able to be his own master.

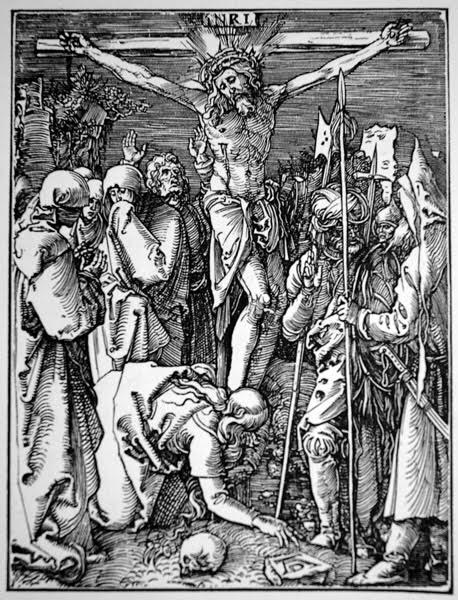

Could there be something more important—and maybe even practical—going on? Although Dürer was meticulous with his writings of journals, letters, family history, and books, he wrote absolutely nothing regarding his Christ like self-portrait. This would suggest that it was something very private, kept just for himself. Was it simply painted for Dürer’s own personal devotional life as a reminder to daily imitate Christ? Or could this self-portrait be a prototype for something in the future, just as The Praying Hands was a pattern for a future work? Interestingly, it is the same face that he uses in the 1511 publication of his Small Passion (depicted left) for the face of Christ, the Second Adam. Could Dürer’s self-portrait have been a preliminary, carefully executed exercise in capturing the face of all mankind made perfect in Christ?

Deaconess Carolyn S. Brinkley is the Director of the Military Project at Concordia Theological Seminary, Fort Wayne, Ind.

Additional information: Dürer’s Self-Portrait (1500) is oil on panel measuring 67×49 cm. It was on public display in the Nürnberg Rathaus from approx. 1528 to 1805 when it was taken to Munich and where it is still housed today in the Alte Pinokothek.

Woodcut Caption: Albrecht Durer’s Small Passion: Crucifixion

[i] Stefano Zuffi, Dürer, (London: Prestel 2012) 58.

[ii] William Martin Conway, The Writings of Albrecht Dürer, (New York: Philosophical Library 1958) xviii.