by Rev. James A. Lee II

In the Small Catechism’s presentation of the Sacrament of the Altar one may be a bit surprised at the amount of attention Luther gives to the words of institution. After all, this is the section wherein that is dedicated to the discussion of the sacrament of Christ’s body and blood, yet Luther speaks about the Words of Institution almost as much as he does the elements. He even goes as far as to say that “next to the bodily eating and drinking” Jesus’ words are “the central thing,” “the head and the chief thing” (das Hauptstück, caput et summa) of the sacrament. How is it that Luther accords so much worth, such great value, to these words? Isn’t Luther guilty of hyperbole? Isn’t Luther overstating his case? After all, this is the sacrament of Jesus’ body and blood.

For Luther the words of institution are given such a place of priority for they are Jesus’ own instituting words. These are Christ’s words of promise, of forgiveness, of life. As Luther writes in his German Mass,

“[Y]ou must above all else take heed to your heart, that you believe the words of Christ, and admit their truth, when he says to you and to all, “This is my blood, a new testament, by which I bequeath you forgiveness of all sins and eternal life. [. . .] Everything depends, therefore, as I have said, upon the words of this sacrament. These are the words of Christ. Truly we should set them in pure gold and precious stones, keeping nothing more diligently before the eyes of our heart, so that faith may thereby be exercised. [. . .] So if you would receive this sacrament and testament worthily, see to it that you give emphasis to these living words of Christ, rely on them with a strong faith, and desire what Christ has promised you in them.”[1]

With these words Jesus institutes the sacrament, mandates its use and reception, consecrates the elements, informs and the Christian of what he receives, strengthens the Christian’s faith and conscience, while providing sustenance for the Christian’s soul and body.[2]

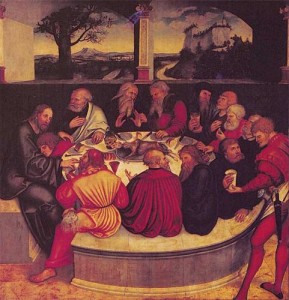

In order to further appreciate why Luther valued the words of institution to this degree it is necessary to remember the controversies that emerged surrounding the Lord’s Supper. On the one hand the churches of the Augsburg Confession were confronted by the medieval Catholic doctrine of the Sacrament that professed that the sacrament of the altar is a sacrifice offered for the sins of the living and the dead. This teaching went on to be ratified at at the Council of Trent (1545–1563), where it was boldly confessed:

“If any one says, that the sacrifice of the mass is only a sacrifice of praise and of thanksgiving; or, that it is a bare commemoration of the sacrifice consummated on the cross, but not a propitiatory sacrifice; or, that it profits him only who receives; and that it ought not to be offered for the living and the dead for sins, pains, satisfactions, and other necessities; let him be anathema.”[3]

The Roman Catholic church had confounded the sacrament of Christ’s body and blood into a sacrifice, offered to the Father, on behalf of the sins of humanity. Against Jesus’ own institution, the sacrament had been distorted into a work offered to obtain the forgiveness of sins, rather than being the means through which Jesus bestowed the forgiveness of sins.

Yet it was not only the Tridentine Catholic church that had confused the reality of the Lord’s Supper. The Reformed churches, while denouncing the sacrificial aspect of the sacrament, extended their rejection to include Jesus’ bodily presence in the bread and the wine. The Reformed confession of 1548, the Consensus Tigurinus, succinctly summarizes the position of the Reformed on the sacrament of the altar and the points of disunity with the Lutherans:

[Article 22] “Therefore we condemn those as false interpreters, who insist that the solemn words of the Lord’s Supper, ‘This is my body; this is my blood,’ are to be taken, in what they call, the exact literal sense. For we hold it out of controversy that they are to be taken figuratively, that it is said of the bread and wine, they are called.”[4]

While the the Reformed could speak of how the believer, by faith, is nourished through Christ, in no manner was this to be understood as if this feeding took place through the presence of Christ’s body and blood in the Lord’s Supper. The Reformed rejected any notion of Christ’s bodily presence in the sacrament.

Amidst the errors of the Roman Catholic sacrificial interpretation and the Reformed rejection of the bodily presence, the Lutherans continued to confess that the Lord’s Supper is the very body and blood of Jesus, given in bread and wine, not as a sacrifice for sins, but for the forgiveness of sins. The foundation and defense of their confession were Jesus’ own mandating words. Like Luther before, the next generation of Lutherans ardently held fast to the words of institution: with these words Jesus instituted this sacrament and shows what is given therein. Luther’s theology of the Lord’s Supper, grounded in the words of institution, was preserved in the following generation of Lutherans. The authors of the 1577 Formula of Concord follow Luther in their fervent confession of the Jesus’ words of institution:

“This very opinion [on the Lord’s Supper], just stated, is founded on the only firm, immovable, and undoubtable rock of truth. It comes from the words of institution, in the holy, divine Word. [. . .] We are certainly duty-bound not to interpret and explain these words in a different way. For these are the words of the eternal, true, and almighty Son of God, our Lord, Creator, and Redeemer, Jesus Christ. . . . With simple faith and due obedience we receive the words as they read, in their proper and plain sense.”[5]

The Formula of Concord holds steadfast to the words of institution for the confessors understood that these words are they very words of the incarnate Lord, with which He gives His body and blood, in bread and wine, to the Church. Apart from these certain words the church risks losing the sacrament, transforming the nature of Christ’s mandate, obscuring the gifts that are thereby distributed. The Formula follows Luther’s lead and doubles down on the Jesus’ instituting words. Jesus gives the sacrament, He gives the words, and He interprets the words. The Formula sees that it is only through the words of institution that one is able to avoid error and correctly receive the Lord’s gifts.

The Rev. James Ambrose Lee II is the assistant pastor of Trinity Lutheran Church, Worden, IL and doctoral candidate at Saint Louis University.

[1] Luther, The German Mass and Order of Service, WA 12: 96, 20–27; LW 53:79–80. Emphasis added.

[2] Luther, Large Catechism, LC V , 23.

[3] Canon III, Doctrina de Sacrificio Missae (1562) in Concilium Tridentinum – Canones et Decreta.

[4] See Consensus Tigurinus (1549): die Einigung zwischen Heinrich Bullinger und Johannes Calvin über das Abendmahl : Werden, Wertung, Bedeutung, eds. Emidio Campi und Ruedi Reich (Zürich: Theologischer Verlag Zürich, 2009).

[5] FC SD VII, 42, 45, in Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions, 812, 813.