by Rev. Aaron Moldenhauer

You may have an idea about who needs to repent, and what they need to do. He needs to stop sleeping around. She needs to clean up her language. Odds are that he or she is not you. You’ve already cleaned up your act, so you’re done with repentance.

The Lutheran Confessions see repentance differently on several points. First, they insist that you need to repent, regardless of who you are. Second, they teach that repentance is not something you do. God works repentance in you. Third, they teach that repentance does not consist only of works, and the Augsburg Confession and the Apology do not include works as part of repentance. How does that work?

In the Augsburg Confession, Melanchthon writes that “strictly speaking, repentance consists of two parts. One part is contrition, that is, terrors striking the conscience through the knowledge of sin. The other part is faith, which is born of the Gospel (Romans 10:17) or the Absolution and believes that for Christ’s sake, sins are forgiven.”[1] In the Apology Melanchthon adds that if someone wants to add as a third part “fruit worthy of repentance, that is, a change of the entire life and character for the better,” he will not oppose that three-part definition.[2] But in the Augsburg Confession and the Apology works are a fruit of repentance. They follow contrition and faith, the two proper parts of repentance.

Contrition

Contrition is “the true terror of conscience, which feels that God is angry with sin and grieves that it has sinned. This contrition takes place when sins are condemned by God’s Word.”[3] Contrition is an interior condition, a fear and terror in the conscience that feels God’s wrath against sin. To give a scriptural example, Melanchthon quotes Psalm 38:4, 8: “For my iniquities have gone over my head; like a heavy burden, they are too heavy for me. I am feeble and crushed; I groan because of the tumult of my heart.”[4]

Contrition in the Lutheran Confessions is passive, worked in man by God’s law. Melanchthon identifies Paul’s language of “putting off the body of the flesh” and God “making dead” as examples of contrition. Faith alone “makes alive.”[5] Dying and rising are works God does in a person.[6] Scripture puts these two works of God together under repentance.[7] Likewise, in the Smalcald Articles Luther speaks of contrition worked by the law. True contrition is passive contrition worked by God’s law, not “manufactured repentance” devised by the person.[8]

Faith

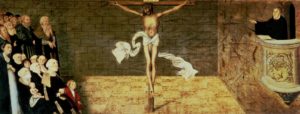

Faith in Christ—the belief that for Christ’s sake, their sins are forgiven—cheers, sustains, and enlivens the contrite. This faith obtains forgiveness, for it grasps the forgiveness of sins offered for Christ’s sake.[9] Melanchthon includes faith as part of repentance. Luther also places faith immediately after contrition. Those who know through repentance (and here Luther uses “repentance” in a narrow sense as only contrition) that they are lost are prepared to receive the Lord and his grace through faith.[10]

Within repentance, the Lutheran Confessions draw careful distinctions to clarify that contrition and works do not obtain forgiveness. Faith alone does.[11] The Formula of Concord excludes contrition and good works from the article of justification. The Formula observes that while faith cannot exist with a wicked intention to sin (that is, in a heart without contrition), and good works follow justifying faith, contrition and works do not merit justification.[12]

Works

What about works? There are two complementary arrangements of works and repentance in the Confessions. The first arrangement appears in the Augsburg Confession and Apology, where good works follow repentance. Works are fruit, commanded by God, that repentance should produce.[13] As noted above, Melanchthon does not object to including works in repentance alongside contrition and faith. Luther includes works in the Smalcald Articles as he summarizes the preaching of repentance: “You are all of no account, whether you are obvious sinners or saints (in your own opinions). You have to become different from what you are now. You have to act differently than you are now acting, whether you are as great, wise, powerful, and holy as you can be. Here no one is godly.”[14] Here works are included with contrition in the preaching of repentance. And no one escapes this call to repent.

Certainty and Repentance

Repentance goes wrong, Luther writes, when it forgets Christ and faith.[15] This happens when repentance is seen only as our works, and when it is sidetracked into debating what is right and what is wrong. No, Luther writes, true repentance throws it all together and says: “Everything in us is nothing but sin.” True repentance teaches us to discern sin by saying: “We are completely lost; there is nothing good in us from head to foot; and we must become absolutely new and different people.”[16] That type of repentance continues throughout the life of a Christian.[17] Such total repentance prepares the heart for Christ and his gifts received through faith.

There is comfort found in the Lutheran understanding of repentance. Including faith in repentance lifts yours eyes off of yourself and a vain attempt to determine if your repentance is genuine enough to obtain forgiveness. Instead, by including faith, the Lutheran Confessions direct your eyes to Jesus, that you may be comforted by the forgiveness freely offered to you in Jesus through faith. This teaching can set you free from doubt, giving you the confidence found in Christ alone.[18]

Further Study

Space permits only this outline of repentance in the Lutheran Confessions. While repentance appears throughout many articles in the Confessions, the key texts for further study are those articles that address repentance at greater length: The Augsburg Confession, article 12; The Apology, article 12 (5–6); The Smalcald Articles, Part 3, article 3; and The Formula of Concord, articles 2, 3, and 5.

The Rev. Aaron Moldenhauer is associate pastor of Zion Lutheran Church, Beecher, IL.

[1] Augsburg Confession XII:3–5. This (and all subsequent translations) from Paul Timothy McCain, Robert Cleveland Baker, Gene Edward Veith, and Edward Andrew Engelbrecht, eds., Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions: A Reader’s Edition of the Book of Concord (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005), 64.

[2] Apology XII (V):28; Concordia, 187.

[3] Apology XII (V):29; Concordia, 187.

[4] Apology XII (V):28–34; Concordia, 187–188.

[5] Apology XII (V):46–47; Concordia, 189.

[6] Here, in Apology XII (V):51; Concordia, 190, the two works are identified as God’s “strange” (sometimes translated “alien”) work of making dead and his proper work of making alive.

[7] Apology XII (V):51–52; Concordia, 190.

[8] Smalcald Articles, III.III:2; Concordia, 298.

[9] Apology XII (V):35–38; Concordia, 188. Melanchthon discusses childlike fear in connection with faith consoling the contrite. Childlike fear is defined as “anxiety that has been connected with faith, that is, where faith comforts and sustains the anxious heart.” This is contrasted with slavish fear, when faith does not sustain the anxious heart. Note how faith here is the source of consolation and comfort for the Christian.

[10] Smalcald Articles, III.III:4–6; Concordia, 298–299.

[11] Apology XII (V):17–20; Concordia, 187.

[12] Formula of Concord, Epitome, III:11; Concordia, 499.

[13] Apology XII (VI):77; Concordia, 209.

[14] Smalcald Articles, III.III:3; Concordia, 298.

[15] Smalcald Articles, III.III:10–21; Concordia, 299–300.

[16] Smalcald Articles, III.III:33–37; Concordia, 302.

[17] Smalcald Articles, III.III:40; Concordia, 302.

[18] Apology XII (V):4–10, 88–90; Concordia, 184–185, 196.