By Dr. Jack Kilcrease

Throughout the 1520s, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V was deeply frustrated by the rise of the Lutheran Reformation.

Although he wished to put an end to the various Protestant movements that had grown up in the empire, he nevertheless found it very difficult to do so in light of a variety of wars he was engaged in with the Ottoman Turks and the League of Cognac. For this reason, Charles was effectively forced to allow the Reformation to spread largely unchecked throughout the 1520s.

Nevertheless, by 1530, Charles had either defeated or made a temporary peace with his enemies. Hence, he was finally able to turn his full attention to the religious issue that had plagued Germany since the Diet of Worms in 1521.

Therefore, in January of 1530, the Emperor called an imperial Diet to meet in the German city of Augsburg in April of that year to decide the religious question.

As part of this imperial meeting, the Lutheran princes were asked to present their religious teachings. Wishing to present a unified front at the Diet, Luther, Melanchthon, and several other Wittenberg reformers met at Torgau in March of the 1530 and drafted a confessional document which came to be known as the “Torgau Articles.”

Since Luther was still officially an outlaw under imperial law, he could not travel to Augsburg to present these articles before the Emperor and the imperial Diet. Instead, a delegation led by Philipp Melanchthon traveled to Augsburg to present the confession of faith before the Emperor, while Luther remained at Coburg Castle.

Once there, Melanchthon revised the articles drafted earlier at Torgau under the advice of a number of theologians and political leaders. The final draft was completed on June 23 and came to be known as the “Augsburg Confession.”

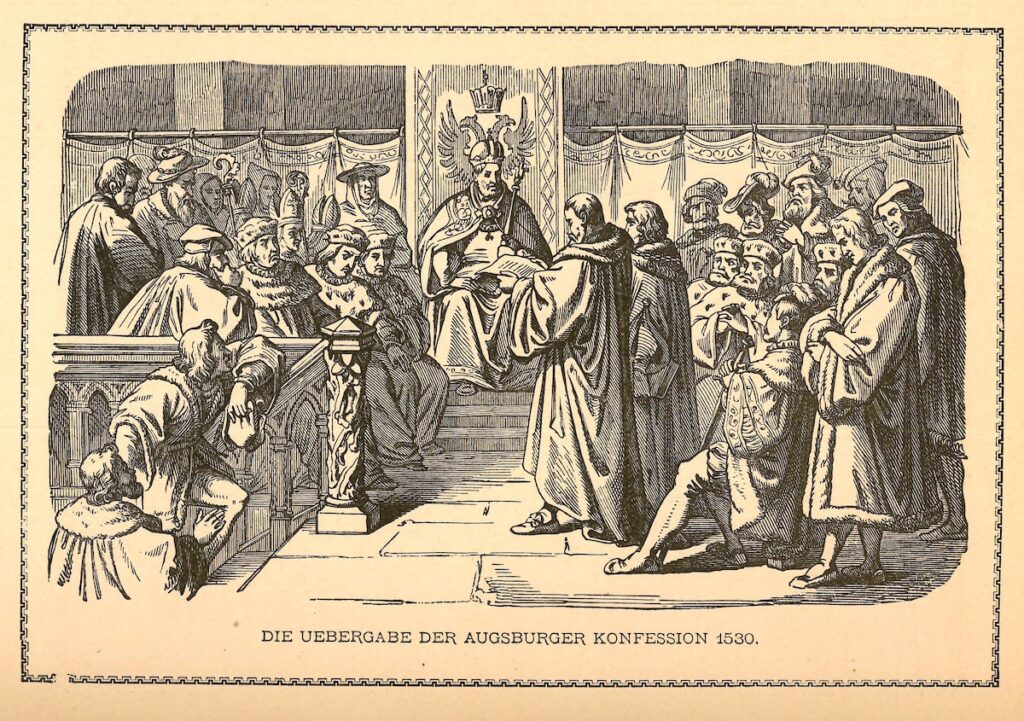

Luther was sent drafts of the revised document as it was composed and approved the revisions and the final draft as well. Although the petition of the Lutheran princes to have the document publicly read was initially refused, the Emperor finally agreed. As a result, Dr. Christian Beyer read the German edition of the Augsburg Confession before Charles V on June 25, 1530.

The Augsburg Confession is comprised of 28 articles. Of these articles, 21 represent a positive presentation of the Christian faith as taught in the Lutheran Churches while the last seven article cover suggested reforms of certain practices of the medieval Church.

Although the ultimate aim of the Augsburg Confession was to summarize the main teachings of the Bible, Melanchthon also wished to emphasize the “catholic” (that is, meaning “universal,” not “Roman Catholic”) nature of Lutheran teaching. Throughout the confession, Melanchthon quotes or makes reference to the theologians and councils of the ancient Church to demonstrate the Lutheran Church’s continuity with early Christian teaching.

Showing the catholicity of Lutheran belief was important because many Roman Catholic theologians had claimed that the Lutherans had broken with the traditional theology of the Church going all the way back to Christ and the apostles.

Contrary to this charge, the Lutherans sought to show that their faith was not only drawn from Scripture, but had been the basic teachings of the Christian Church throughout the ages. It was only later that the medieval Church corrupted the true faith through unbiblical and uncatholic innovations. This argument also carries over into the last seven articles that deal with reforms.

With a few exceptions, most of the reforms proposed by Melanchthon involve rolling back changes that had been made to Church teaching and practice in the 11th century by Pope Gregory the VII and his followers during a period often called the “Gregorian Revolution” by Church historians.

Although it is highly unlikely that modern Christians will ever be called upon to give an account of their faith in quite the same manner as the Wittenberg reformers did at Augsburg, the presentation of the Augsburg Confession may still serve as an important model to the Christian life of faith.

Paul teaches us: “If you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved” (Rom. 10:9).

For this reason (although Christians do not earn their salvation by confessing Christ publicly), faith necessarily gives rise to a public confession of faith through words and actions. If we believe in Jesus and the salvation he offers, we will confess that faith publicly, knowing that whatever the negative social, political, or personal consequences, the forces of this world do not have the power to control our ultimate fate. Christ has already overcome the world (Jn. 16:33) and we need not fear confessing the faith boldly.

Dr. Jack Kilcrease is a member of Our Savior Lutheran Church in Grand Rapids, Mich.