by Rev. Christopher Maronde

The Formula of Concord is a remarkable, even miraculous document. It did what few documents in the history of the Christian Church have ever done: it brought unity, it brought together a Church, the Lutheran Church, which had been ravaged by dissention and division. The Formula did not paper over division, it did not tell the warring parties to ‘agree to disagree,’ it wasn’t a search for the lowest common denominator. No, the Formula of Concord brought unity by examining each and every controversy and resolving them according to the Word of God and the accepted confessions of the Lutheran Church.

There is one more miracle here. Philip Melanchthon, through his own vacillations on certain doctrines and his irenic spirit that ended up seeking peace at the expense of the truth, had exacerbated many of the controversies that rocked the Lutheran Church in this era. It would not be his enemies, however, who would heal these wounds, but his students, his friends, those who highly respected him but yet saw the weaknesses in his theological approach.

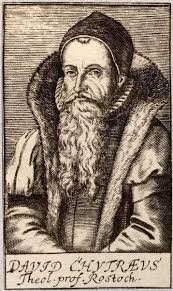

One such student was David Chytraeus, a man who sat at the feet of Melanchthon and Luther, a man who lived in Melanchthon’s home, a man who to the end of his life would not speak a harsh word against his teacher. Not only did he study under Melanchthon in Wittenberg, he even heard Dr. Luther lecture on Genesis, the aging reformer’s crowning work. A talented exegete, from his post as professor at the University of Rostock in Mecklenburg he not only published numerous works that were extremely popular, but was a towering figure at his own university.

This brilliant theologian was called upon to utilize his considerable talents in service of the Church. He prepared documents at the various stages of the process, and he participated in the meetings where the Formula was painstakingly put together. From his pen came two of the most important articles in the document: free will and the Lord’s Supper. In the article on free will, the same procedure is followed as with most of the other articles: the controversy is stated, the positions of the various sides are summarized, and then the proper confession according to God’s Word is given. Chytraeus quotes from the Scriptures, from the Augsburg Confession, its Apology, the Large Catechism, and other works of Luther; in other words, the confession of the truth is undeniably Scriptural, as the Lutherans have understood those Scriptures. And the conclusion? Man has no free will toward God.

“We believe that in spiritual and divine things the intellect, heart, and will of unregenerate man cannot by any native or natural powers in an way understand, believe, accept, imagine, will, begin, accomplish, do, effect, or cooperate, but that man is entirely and completely dead and corrupted as far as anything good is concerned.” (FC SD II, 7)

Only Jesus can make the dead alive.

“Just as little as a person who is physically dead can by his own powers prepare or accommodate himself to regain temporal life, so little can a man who is spiritually dead, in sin, prepare or address himself by his own power to obtain spiritual and heavenly righteousness and life, unless the Son of God has liberated him from the death of sin and made him alive.” (FC SD II, 11)

The article on the Lord’s Supper was deemed necessary both to present an even stronger confessional bulwark against error and to stop those who bore the name Lutheran but held to a less-than-Lutheran view of the presence of Christ in the Supper. Chytraeus, drawing once again from the Scriptures and the existing Lutheran confessional documents, and the private writings of Luther, makes a confession that is clear, direct, and cuts through any equivocation.

“For as in Christ two distinct and untransformed natures are indivisibly united, so in the Holy Supper the two essences, the natural bread and the true, natural body of Christ, are present together here on earth in the ordered action of the sacrament.” (FC SD VII, 37-38)

In the end, Chytraeus was somewhat dissatisfied with the Formula of Concord. He complained, clearly exaggerating, that the articles he had originally composed had been so heavily edited that nothing remained of his original composition. However, despite any hurt feelings, Chytraeus put away his pride and dedicated himself to the defense and propagation of the Formula, participating in debates and encouraging signatures. This, just as much as the way the document was written, illustrates the tone and intent of the Formula of Concord.

The Formula’s task, taken up by men like David Chytraeus, seemed irenic and naïve to the extreme. At least, that is what most ecumenically minded people today think. Many can only conceive of unity that is achieved by ignoring doctrinal divisions, or dismissing their importance. This was not the path of the Formula of Concord. For the formulators, the road to unity could only be through the study and bold confession of the Word of God. And the very survival of the Lutheran Church to this day is testimony that, by God’s grace, their task succeeded.

The Rev. Christopher Maronde is associate pastor of Good Shepherd Lutheran Church, Lincoln, Nebraska.