by Rev. Dr. Jonathan Mumme

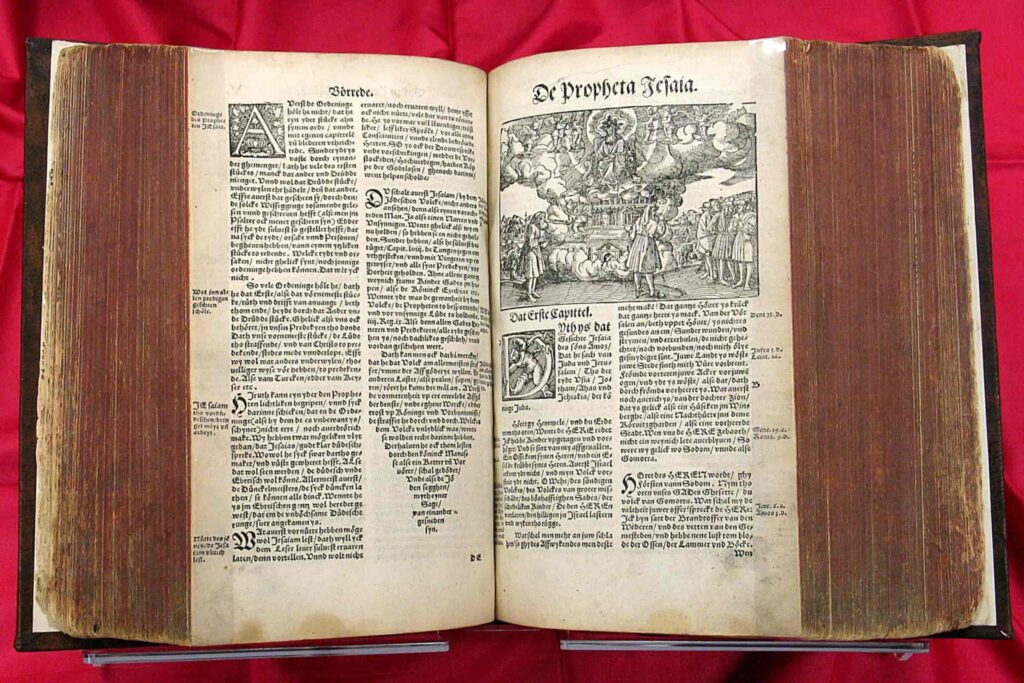

With Gutenberg’s invention of movable type printing and waxing literacy especially among the urban population, Christian interaction with the Bible entered a new phase in the Reformation era. In this, Martin Luther played a direct hand, not only with his translation of the Bible, but also with his introductions to the various books of the Bible.

Luther came to his task as translator of the Bible and publisher of biblical introductions by way of his dual vocations of university professor and city preacher. As an introduction to a series of sermons written in the same year that he would publish a first translation of the New Testament along with prefaces (1522), Luther gave preachers, hearers of sermons, and eventually readers of the Bible “A Brief Instruction on What to Look For and Expect in the Gospels.”[1]

The first thing to note about the interacting with the gospels (that is the accounts of the Evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) is that the each of these, as indeed other writings of the New and Old Testaments, has to do with the Gospel. “One should thus realize that there is only one gospel, but that it is it is described by many apostles.”[2] Thus, in the writings of the evangelists and in other writings of the Sacred Scriptures, one is to seek and expect “nothing else than a discourse or story about Christ. … telling who he is, what he did, said, and suffered.”[3] This singular gospel in a nutshell has to do with the Son of God becoming man, suffering, dying, being raised, and being established as Lord over all things.

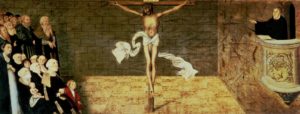

This “joyful, good, and comforting ‘message’”[4] delivers Christ as a gift. Luther seems to guess (and one might add – guess rightly – given how fallen human beings are hardwired) that people are most inclined to be looking for a main message of the Scriptures that can be classified “example”, something that stands as a guide to be followed and a code of rules to be obeyed. Even Christian human beings are inclined to make the gospels into a guide and behavioral code. However, primarily and essentially, the gospel presents and delivers Christ as a gift “that God has given you and that is your own. This means that when you see or hear of Christ doing or suffering something, you do not doubt that Christ himself, with his deeds and suffering, belongs to you. On this you may depend as surely as if you had done it yourself; indeed as if you were Christ himself.”[5] With Christ so received as gift, and with heart and conscience happy and secure, the Christian also can receive Christ as an example, which will exercise the Christian and make him or her a gift to fellow human beings.

Luther, the preacher become Bible translator, never lost sight of the fact that Christ delivered as a gift, even in an age of printing and growing literacy, was fundamentally effected by preaching. When he gave his brief instruction in 1522 on what to look for and expect in the gospels he was doing this for a series of sermons on the gospel lessons for the weeks of Advent and Christmas. The gospel, he notes, “should really not be something written, but a spoken word which brought forth the Scriptures, …” Christ’s gospel is “good news or proclamation that is spread not by pen but by word of mouth.”[6] In preaching, which is related to and leads to profitable reading of the Scriptures, Christ can be and is fully gift in a unique way. “For the preaching of the gospel is nothing other than Christ coming to us, or we being brought to him.”[7] It is on the receiving end of Christ-gifting preaching that the Christian is resourced to further proper and profitable interaction with the Scriptures.

The Rev. Dr. Jonathan Mumme is Assistant Professor of Theology at Concordia University-Wisconsin in Mequon, Wis.

[1] LW 35:117-24; WA 10 I/1:8-18.

[2] LW 35:117; WA 10 I/1:9,6f.

[3] LW 35:117f; WA 10 I/1:9,15-17.

[4] LW 35:120; WA 10 I/1:12,2.

[5] LW 35:119; WA 10 I/1:11,14-18.

[6] LW 35:123; WA 10 I/1:17,7-12

[7] LW 35:121; WA 10 I/1:13,22-14,1.