by Rev. Dr. Jonathan Mumme

One might say that for the facets, topics, or loci of Christian theology there are seasons. There is, for example, nothing more to Christology than the confession that Jesus, the Son of Man and the Son of the Living God, is Lord.[1] But the truth of that full and mysterious confession unfolds, subsequently, over against error—such as Gnosticism, Arianism, Nestorianism, Eutychianism, and the like. Christology, though never done flowering and unfolding over against error, did have something of a season in the third and fourth centuries. Similarly, ecclesiology—that is, the doctrine of the church—begins and is full with Christ’s own foundation of the church,[2] yet it too has subsequent seasons, in which it unfolds. The sixteenth century belonged to such a season.

The Western Church, prior to the Lutheran Reformation, had been arguing about the church. Was its top instance of decision-making authority, for example, the Roman Curia or a (properly convened) council? The question of what the church is, and where it is to be found, was pressed even more with two popes (in Avignon and in Rome) being deposed by a council that attempted to set a third up as the real pope.[3] In the sixteenth century questions of who and what the church is, and where it is to be found, pressed again as a squabble between Augustinians and Dominicans became a row between northern German Evangelicals (today known as Lutherans) and Romanists; then an outright schism of the Western Church came to threaten and finally transpired. Nothing truly Christian is ever a breakaway movement, so while the Romanists lofted charges of heresy and apostasy at the evangelical reformers, they were wont to point out that “we have remained faithful to the ancient church, indeed, that we are the true ancient church and that you have fallen away from us,”[4] and that nothing taught in their churches “depart[ed] from the Scriptures or the catholic church, or the church of Rome insofar as [its doctrine] is known to us from [its] scriptures.”[5]

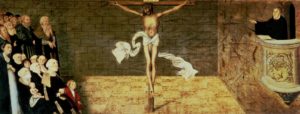

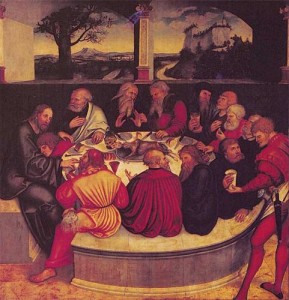

The claim of these evangelicals to be the church was founded on what they could sometimes call “the marks of the church”. That communion of saints that hears the voice of Christ and trusts him for its standing with God is the church.[6] This hearing of faith and holiness of the saints results from Christ’s word being preached and his holy gifts being administered to people. As shorthand, one might say that the Gospel preached and the sacraments administered mark the church precisely because through them the Holy Spirit makes and sustains the church. In both the Augsburg Confession and the Smalcald Articles the church is presented as a reality not out in front of these marks, but as called into existence through their ministerial delivery.

Certain holy things mark the communion of saints or holy ones. How many of these holy things there are can vary in the reformers’ discussion. In his 1539 treatise, On the Councils and the Church, Luther numbers seven holy-making factors: to the preached word, baptism, the sacrament of the altar, the keys and confession, and the making of ministers who deliver such gifts, he adds prayer and the cross.[7] Under “prayer” Luther indicates the liturgical and catechetical forms through which Christians come to learn the faith by speaking and singing its content. The cross marks the church because it always suffers with Christ and as Christ’s, thereby being conformed to Christ.

Far from being some nebulous concept and invisible reality with little or no definite connection to the solid world of human experience,[8] the Lutheran reformers pointed to an identifiable, locatable church, which was Christ’s own church as his words rattled ears, as his gifts met and hallowed embodied sinners, and as those so touched came to speak and sing of their incarnate Lord, and to suffer alongside him.

The Rev. Dr. Jonathan Mumme is assistant professor of theology at Concordia University-Wisconsin.

[1] See Mt 16:13-16 and 1Cor 12:3.

[2] Mt 16:18; cf. 1Cor 3:11.

[3] Such happened at the Council of Pisa in 1409.

[4] Martin Luther, Against Hans Wurst (1541); WA 51:479,17-18; LW 41:194.

[5] Conclusion to the first part of the CA, paragraph 1.

[6] See CA VII:1 and IV along with SA III,xii:2.

[7] WA 50:624,4-53,15 LW 51:143-78. Two years later, in Against Hans Wurst, Luther noted honoring civil authority, preserving the estate of marriage, and the ability to suffer without shedding blood themselves also characterize Christians and point to where the true church may be found; WA 51:476,26-487,6; LW 51:193-99.

[8] Cf. Ap VII:20.