by Deac. Betsy Karkan

Sola Scriptura: Two simple words to summarize one of the foundational teachings of the Lutheran Reformation. In them Martin Luther and other reformers argue that the Bible is the inspired and inerrant Word of God and that it alone is the sole rule and norm of all Christian faith and practice. Though simple in themselves, the impact of these words on doctrine and practice within the church was far from it. Perhaps one of the most significant outcomes stemming from this teaching was the work of translating the Bible—which Luther referred to as the “cradle wherein Christ is laid”[1]—into the common languages of the people, making the Word of God accessible to all.

Today most modern societies would find it hard to imagine a time when the Holy Scriptures were not accessible to them in a language they could understand, but to the people at the time of the Reformation this was the accepted norm. In the very places God had promised He would always be present—His Word and His Holy Sacraments received in the Divine Liturgy—only the clergy and literate upper classes could receive them in a language they understood. Luther and many other reformers opposed the assertion by the Roman Catholic Church authorities that the Word of God could only be correctly interpreted by these elite and that the

König, Gustav Ferdinand Leopold. 1900. The life of Luther in forty-eight historical engravings. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House.

simple common folk could only receive it through their instruction. The claims which stated the simple would be led astray if they were to receive the Scriptures in their own language primarily served to manipulate and control the masses by leaving them in ignorance. Luther would agree with the sentiments of Erasmus who stated that, “Christ wished His mysteries to be published as openly as possible” when he wrote in his letter to John Lang, “I wish every town would have its interpreter, and that this book alone, in all languages, would live in the hands, eyes, ears and hearts of all people.”[2] Confronted with corruptions in the church, Luther believed that these Holy Scriptures, along with the Eucharist and the liturgy, had been held “captive” from the common people. Using a language only those with power and influence could understand, many false doctrines and practices were being introduced with little objection. As a result, many were being deprived of this life-giving Word and truly led astray. As Luther’s arguments against these falsehoods gained attention in the public square it became increasingly necessary to have the Scriptures available to the people to allow them to have an informed decision.

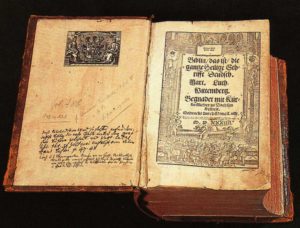

Luther began his translation of the New Testament into German while in exile at the Wartburg Castle. In just 11 short weeks, Luther completed his September Edition of the New Testament in 1522. In 1534, Luther and his colleagues completed an entire translation of the Bible into German commonly known as the Luther Bible. Though it was not the first translation of the Bible into German it is considered by many to be the most influential. Not only did Luther use the spoken German of the common people, but he and his colleagues also based their translations on original manuscripts using such works as Erasmus’ critical Greek edition of the New Testament rather than the Roman Catholic Church approved Latin Vulgate translation.

The movement to get the Scriptures into the language of the people was not limited to Germany however, with Protestant translations popping up all over Europe throughout the 16th century. These are distinct for using The Luther Bible or original Greek and Hebrew manuscripts as the basis for all or some of their translation. The first Reformation translation of the Bible into the English language was begun by William Tyndale, “the Father of the English Bible.” He not only was the first to use the original languages as the source for his English translation, but he is also the first to utilize the printing press in England in order to have his translation mass produced. It is possible that Luther and Tyndale met in Wittenberg when Tyndale fled England to the continent in 1524 and that Luther may have even assisted him in his translation work while Luther was working on his own translation of the Bible. It is clear though that both Erasmus’ and Luther’s work had a significant influence on Tyndale’s work, and is seen in his adoption of various words, phrasing and even Luther’s ordering of the books of the New Testament. Martyred in 1536, Tyndale never completed a full translation of the Bible, but his work was used by Myles Coverdale in the development of the Coverdale Bible (1535) and The Great Bible (1539) which was the first authorized edition of the Bible in English. Coverdale was also involved with the translation of the famous Geneva Bible (1560) which is considered to be the most outstanding English translation of the Reformation. To this day, Tyndale’s translation, influenced by Luther, forms the basis for 90 percent of the King James New Testament and 75 percent of the Revised Standard Version.[3]

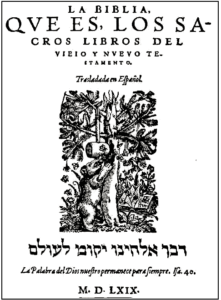

In other parts of Europe more work was being done. The first French translation of the Bible accused of having Protestant leanings was The Antwerp Bible (1530) completed by French theologian Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples still using the Vulgate. Shortly after in 1535, French Reformer Guillaume Farel commissioned Pierre Robert Olivétan to produce the first true protestant translation in French known as the Olivetan Bible or the Neuchiltel Bible. In Holland, the Bible was translated in full by Jacob van Liesveldtin in 1526 using Luther’s translation as well as parts of the Vulgate and is considered to be the first “complete Bible with Lutheran characteristics”[4] in Dutch. The Emden Bible or Biestkens Bible (1558), translated by Mierdman and Gheyliaert was not the first printed in Dutch but is the “first specifically claiming to be modeled on Luther.”[5] Bishop brothers Laurentius and Olavus Petri, using Luther’s Bible, are credited with translating the Gustav Vasa Bible (1541), the first complete printed Bible in Swedish. In Denmark, Christiern Pedersen’s 1543 protestant translation of the Bible was used along with The Luther Bible and Bugenhagen’s Low-German Bible to produce the first complete Danish Biblia or Christian III Bible printed in 1550 by Ludwig Dietz. In Iceland, the New Testament based on The Luther Bible and Vulgate was translated by Oddur Gotskálksson in 1540, and is the first book printed in the Icelandic language. Later on in 1584, Lutheran Bishop Gudbrandur Thorláksson would complete the first full Icelandic Bible translation called Gudbrandsbiblia. Finally, in 1569, Spanish Reformer Casiodoro de Reina translated the earliest complete Bible translated into Castillian Spanish known as the Biblia del Oso or the Bible of the Bear. Referred to as the King James Version of the Spanish Bible, this translation has been the most influential of all Spanish versions of the Bible and revised versions of it are still in use to this day and known as the Reina-Valera Bible.

Thanks to the combined impact of the printing press and the urgency of the Reformers to translate the Bible into many languages, generations of people have been able to receive the gifts of the Gospel through the written word in their own language. This work however is not done, and still continues so that one day Luther’s wish that every home may hold the cradle of Christ in their language may become a reality.

Deaconess Betsy Karkan serves at Concordia University-Chicago.

[1] LW 35:236

[2] LW 48:356

[3] Henry Zecher. The Bible Translation That Rocked the World (1992). http://www.christianitytoday.com/history/issues/issue-34/bible-translation-that-rocked-world.html

[4] Francis, T. A. (2010, Nov 5). The Linguistic Influence of Luther and the German Language on the Earliest Complete Lutheran Bibles in Low German, Dutch, Danish and Swedish. Studio Neophilologica, 72(1), pp. 75-94.

[5] Ibid