by Rev. Jesse Burns

In the year 1529, two prominent theologians of the Reformation, along with a cast of important colleagues from both sides, came face to face in the city of Marburg, Germany for a discussion. This meeting is known as the Marburg Colloquy. The goal of the colloquy, largely organized by Phillip of Hesse, was to politically unite all “Protestants” in an effort to stand together as a united federation against Roman Catholic rule. Those two prominent theologians were Dr. Martin Luther of Wittenberg and Ulrich (Huldrych) Zwingli, the Swiss reformer from Zurich, Switzerland.

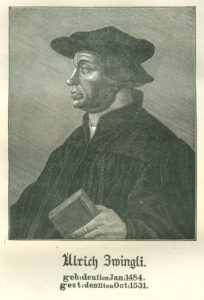

Ulrich Zwingli was born on January 1, 1484 in Wildhaus, Switzerland. He received a Master of Arts degree from the University of Basel in 1506. Later in that same year, Zwingli was ordained a priest in Glarus, where he served for ten years. In 1518, after a two year sabbatical, he took up parish duties in Zurich, where he became the chief reformer of the Swiss reformation.

At the University of Basel, Zwingli was trained in the theological system of Thomas Aquinas, in which “he remained even as a reformer—a Thomist for whom revelation can never contradict reason.”[1] This would be an important difference between him and Luther. Zwingli was also heavily influenced by the Dutch humanist Erasmus, who had a rationalistic approach to Scripture.

As a citizen of the Republic of Zurich, Zwingli was adept in the ways of politics. He used his political prowess as a means to bring about his ideas for reformation. Zwingli, like his Roman Catholic counterparts, held that secular and ecclesiastical power went together. Reform could be carried out using political force. Luther, on the other hand, did not believe that a reform of the Church could be accomplished by political force but only by the Gospel. Tragically, this mixture of his ecclesiastical office and his political ideals led to Zwingli’s untimely demise. On October 11, 1531 Zwingli was killed on the battlefield of Kappel, Switzerland, while serving as a chaplain in a conflict between Protestant and Catholic forces.

Whereas Zwingli held that revelation and reason could not contradict, Luther understood that God’s revelation in Holy Scripture often contradicts human reason. Though Luther was well trained in philosophy, he took his stand squarely in the words of Holy Scripture. This meant that when God’s revelation contradicted human philosophical understanding, Luther didn’t try to reconcile the two. He simply let the Word of God stand as it was.

In an effort to unify the Protestant lands against Roman Catholic forces, Phillip of Hesse sought an agreement, or at least a compromise for the sake of political expediency, between Luther and Zwingli. Over the previous few years, a serious theological dispute had arisen over whether or not the body and blood of Christ are truly present in the bread and wine.

Phillip called the two parties together at Marburg. Zwingli, the politician, came ready to compromise while Luther came ready to confess. Fifteen points of doctrine were discussed and the two sides found agreement on 14. However, there was one point that the two could not agree upon: how to interpret the words of Jesus, “This is My body.”

Zwingli and his colleagues argued that the bread and wine only “signify” or “represent” Jesus’ body and blood, which, they argued, were not capable of being at the right hand of God the Father in heaven and in bread and wine on the altar at the same time,. Because for Zwingli revelation cannot contradict reason he made his argument for the bread “representing” Jesus’ body from passages of Scripture other than those directly connected to Jesus’ institution of the Lord’s Supper, especially John 6.

Luther and his colleagues, on the other hand, argued that the words of Jesus, with which He instituted the Lord’s Supper, clearly teach that the bread, received into the mouth of those who eat it, is—not signifies, nor represents—the body of Christ. For Luther, Christ’s words must stand as they are revealed to us in Holy Scripture. “Is” cannot be turned into something else.

This incident was not the end of the colloquy, by any means. The discussions continued on. However, it serves as an excellent picture of how the debate played out. No matter where Zwingli took the discussion, Luther returned to the words of Jesus, “This is My body.” Luther insisted that Zwingli prove that “is” must mean “signifies,” which the Swiss reformer could not do.

Because of this failure to come to an agreement on the presence of Christ in the Holy Supper, the unity that Phillip had hoped for did not materialize. Some might view this as a political failure. However, Marburg was anything but a failure, for the truth of Scripture was confessed over and against error, and the words of Christ still stand today.

The Rev. Jesse A. Burns is pastor of Redeemer Lutheran Church, Ventura, Iowa.

[1] Sasse, Hermann. This Is My Body: Luther’s Contention of the Real Presence in the Sacrament of the Altar. Adelaide: Lutheran Publishing House, 1977., page 93.

[2] Ibid., 207.