by Rev. Anthony Dodgers

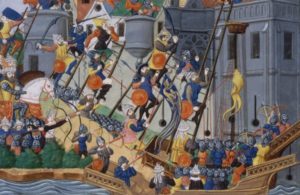

In 1453, Constantinople, the capital city of the Byzantine Empire, fell to the Muslim Ottoman Turks. This marked a decisive end for the eastern Christian empire. Throughout the late-1400s and 1500s, the Ottoman Turks took the lead in the Islamic world. Eventually their empire would stretch east across Asia Minor (Turkey) through Syria to Persia, and south through Arabia, Egypt, and north Africa. But the Turks also pressed westward into Europe, conquering Greece and the Baltics. In 1526, the King of Hungary was killed in battle, and in 1529, the Turks began their siege of Vienna, Austria, the home of the Hapsburgs and a seat of power for the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. Islam was pounding on the gates of western Europe, and many Christians feared that they might give way at any moment to Turkish domination.

Meanwhile, Martin Luther had been pounding on a different door. By the 1520s, the Reformation of the Church was well under way, but Luther was not only concerned with theological debates and church life. He also spoke on the important concerns of society and the civil government, applying Scripture to the hot topics and current events. In 1529, Luther published a treatise called On War Against the Turk (Luther’s Works, Vol. 46, pp.161–205). In this work, he distinguishes between the two men who should fight against the Turk, “and there ought to be only two: the one is named Christian, the other, Emperor Charles” (p.170). In this article, we will hear Luther’s advice for the civil government. In Part 2, we will hear his advice for the Christian.

When the Hungarian king was defeated in 1526, he had been accompanied by an ecclesiastical army led by sword-wielding bishops. But Luther argues that any war against the Turks should not be a religious crusade led by the ministers of the church. “If I were emperor, king, or prince and were in a campaign against the Turk, I would exhort [and even force] my bishops and priests to stay at home and attend to the duties of their office, praying, fasting, saying mass, preaching, and caring for the poor, as not only Holy Scripture, but their own canon law teaches and requires” (pp.167–8). Luther follows Scripture in teaching that God has given authority to the civil rulers, not the church, to punish wickedness and wage war. So, while he hopes that all temporal rulers would also be Christians, he wants “to keep a distinction between the callings and offices, so that everyone can see to what God has called him and fulfill the duties of his office faithfully and sincerely in the service of God” (p.166).

Luther argues it is the emperor’s duty to wage war, but that doesn’t mean he can attack whomever he wants. The emperor is under God’s order and there are just causes for the emperor to fight the Turk; chiefly, “the Turk is attacking his subjects and his empire, and it is his duty as a regular ruler appointed by God, to defend his own” (p.184). When the emperor takes up this task in obedience to God, he also serves his neighbors by providing protection for his subjects and a good conscience for his soldiers. This is why it is important that the civil government take up this task, not the church: “If there is to be war against the Turk, it should be fought at the emperor’s command, under his banner, and in his name. Then everyone can be sure in his conscience that he

is obeying the ordinance of God, since we know that the emperor is our true overlord and head and that whoever obeys him in such a case obeys God also… If he dies in this obedience, he dies in a good state, and if he has previously repented and believes in Christ, he will be saved” (p.185). Luther gives further practical advice on why and how to wage war, warning the emperor and those who serve him, that they should not go to war for the “winning of great honor, glory, and wealth, the extension of territory, or wrath and revenge… By waging war for these reasons men seek only their own self-interest” (p.185). He also advises that we should “not insufficiently arm ourselves and send our poor Germans off to be slaughtered. If we are not going to make an adequate, honest resistance that will have some reserve power, it would be far better not to begin a war” (p.201). Luther’s advice on the just causes for war with the Muslim nations of his day are still good advice for civil governments today. A just government’s chief concerns should be obedience to God and protection for its own people. Even secular or unbelieving rulers unknowingly serve God when they do their duty to their citizens.

Ultimately, the Christian knows not to place his trust in earthly rulers. We also hope and pray that the rulers know not to place their trust in their own might. While we work and fight for temporary peace and security in this world, for the defense of the helpless, the maintenance of justice, and the flourishing of virtue, our hopes are not pinned on establishing a perfect kingdom on earth. We have another King who shall not fail us. This is what Luther says about the advice he offered: “If it helps, it helps; if it does not, then may our dear Lord Jesus Christ help, and come down from heaven with the Last Judgment and strike down both Turk and pope, together with all tyrants and the godless, and deliver us from all sins and from all evil. Amen” (p.205). It is to this King that we shall turn to in Part 2, as we learn from Luther what Christians in particular should do when faced with the threat of Islam.

The Rev. Anthony Dodgers is pastor of Immanuel Lutheran Church, Charlotte, Iowa.